Culturas del Cantri

2022

studio propositions

advisors jen maigret

institution university of michigan - ann arbor

abstract

Alto Comedero, the southernmost neighborhood of Argentina’s northernmost city San Salvador, is home to the indigenous Organización Barrial Túpac Amaru.

The OBTA managed to secure government funding to self-build a neighborhood. Their novel approach to political organization and material production allowed cultural structures to emerge from surplus—a swimming pool, dinosaur park, schools and more redefined their sense of place. The group gained power and lost favor with a newly elected government, leading to criminalization and a complete freeze of national support.

This project reimagines OBTA’s fate in a speculative Scenario B, beginning when funds were received.

How can urban design co-produce resilient fabrics capable of withstanding tense sociopolitical shifts in a long-term project regarding historically marginalized people?

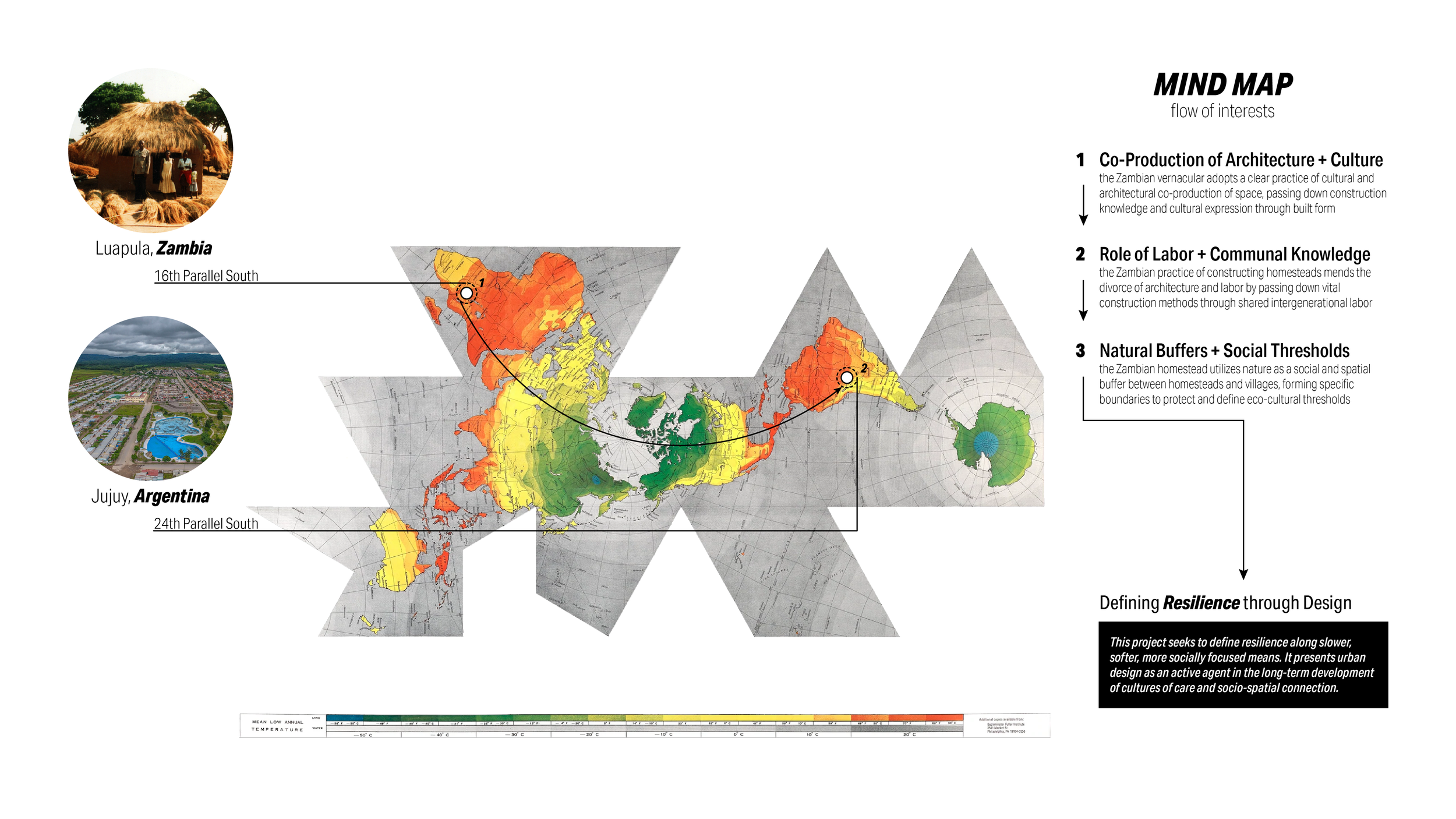

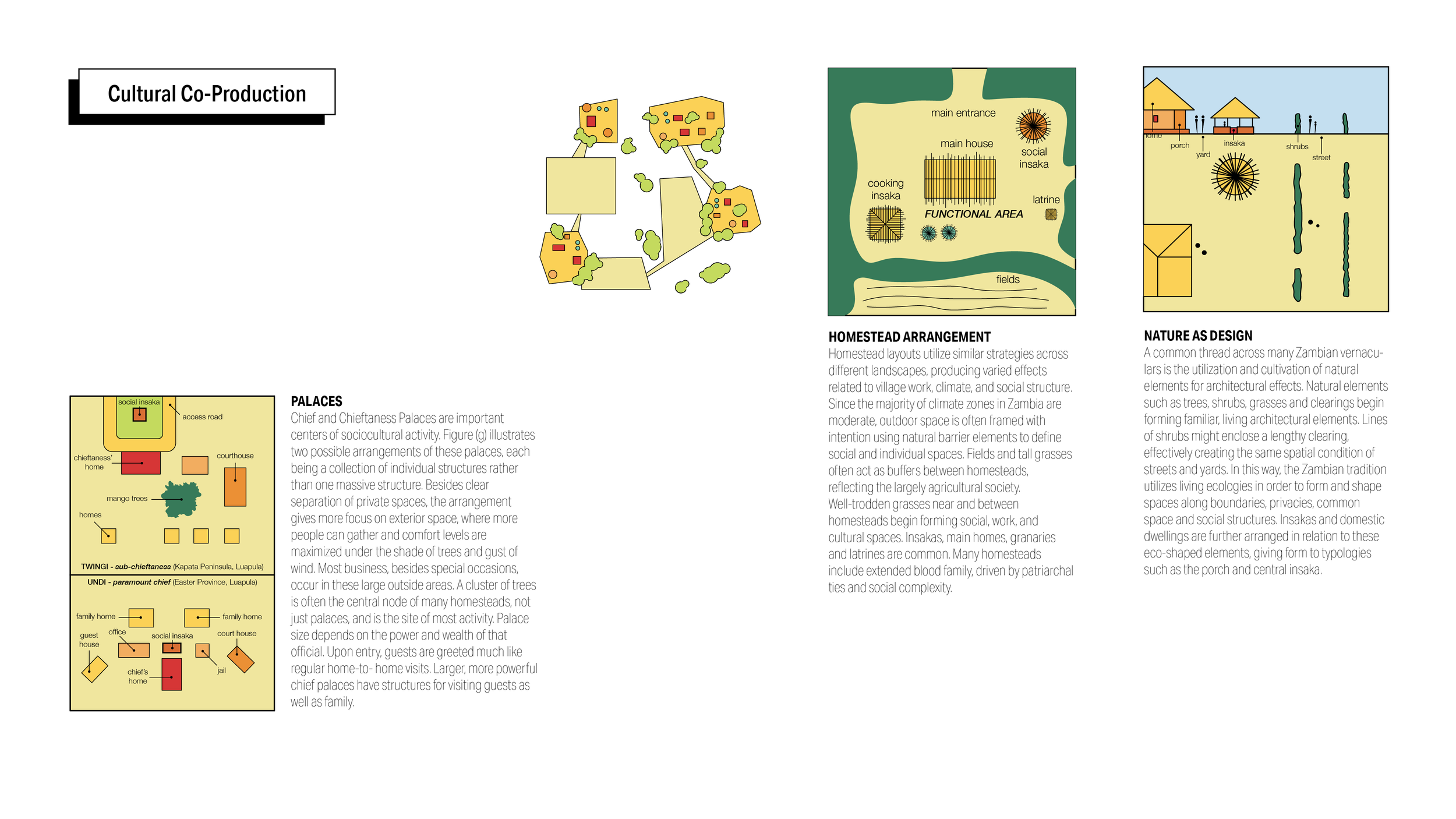

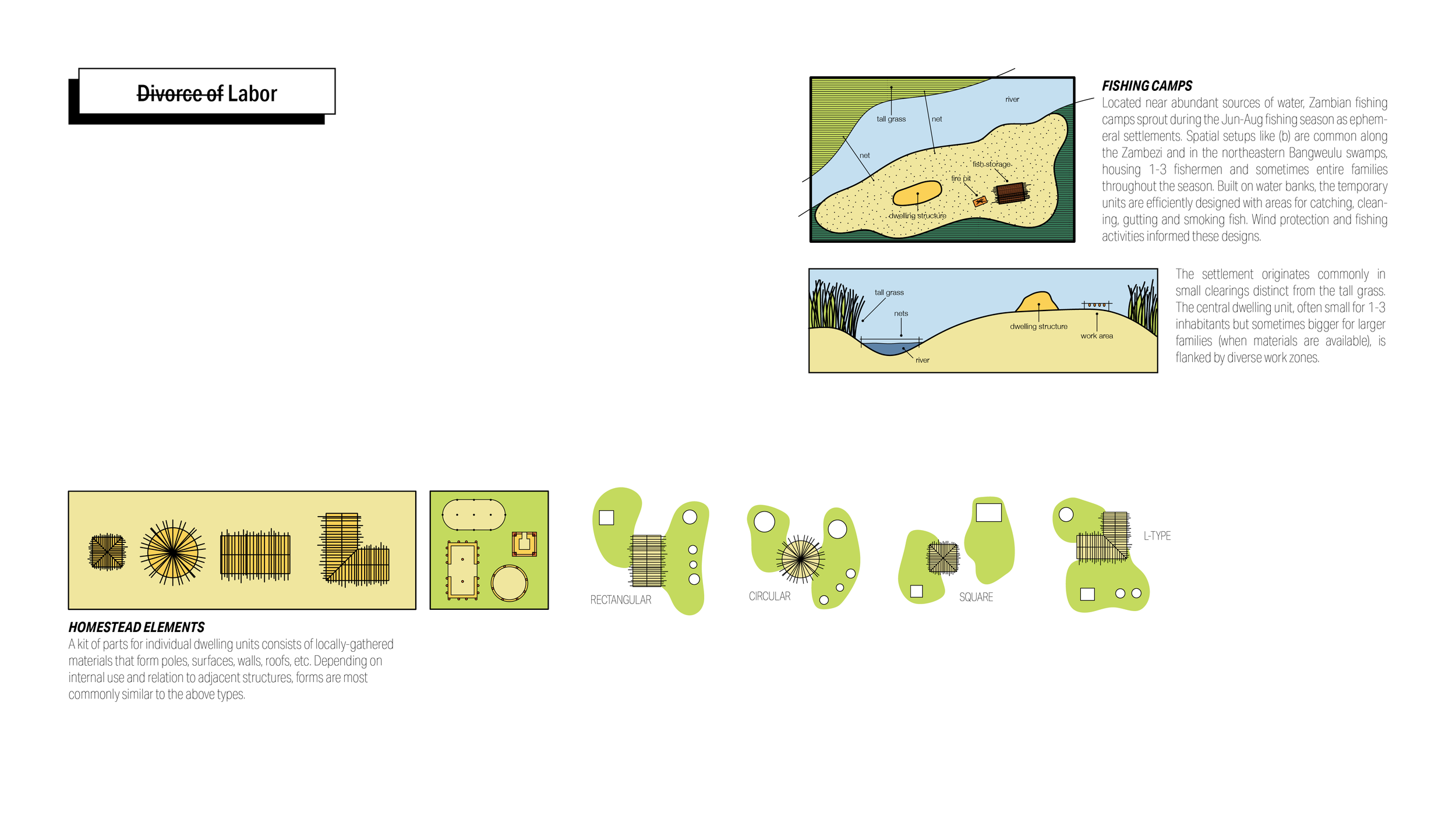

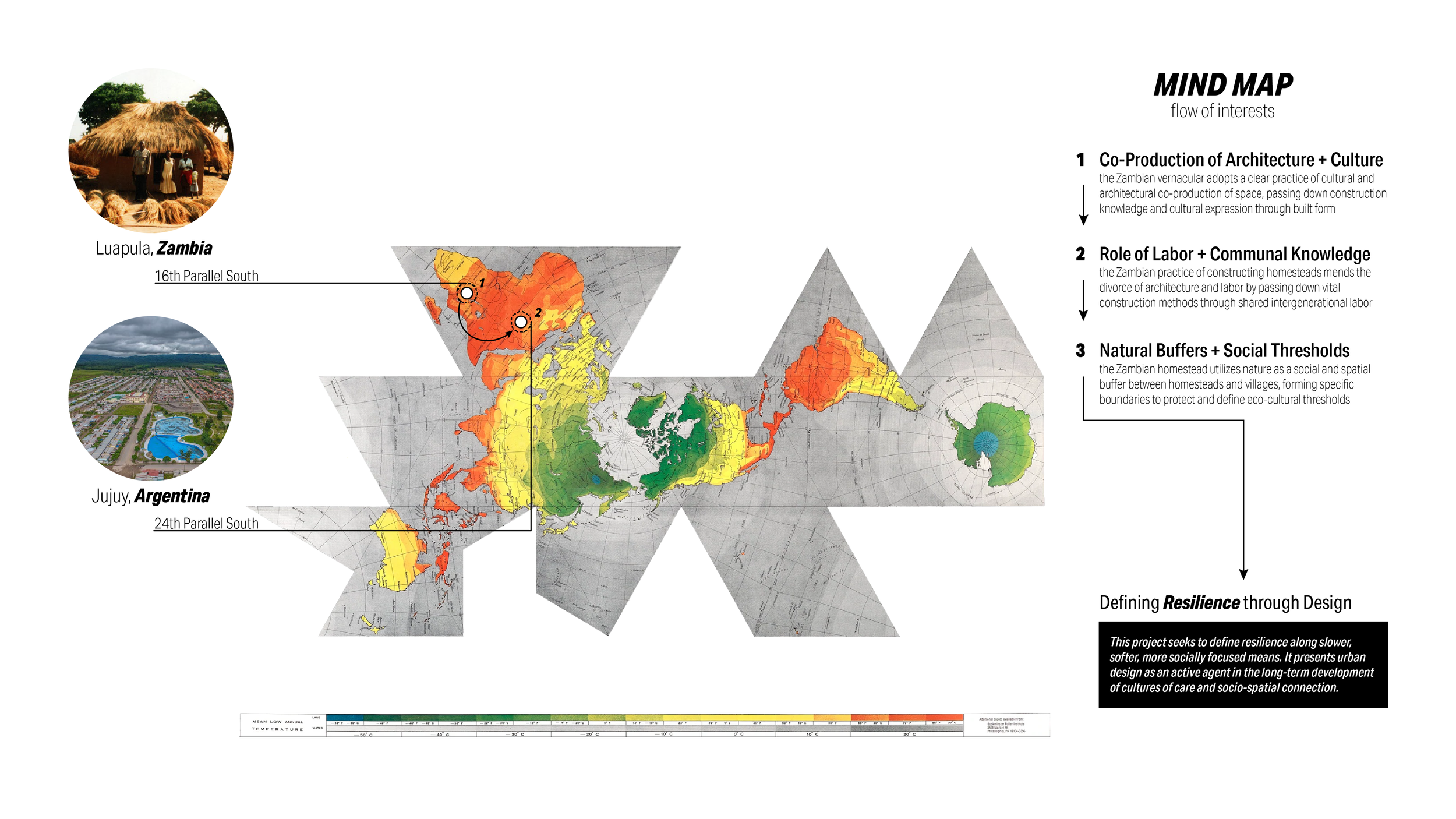

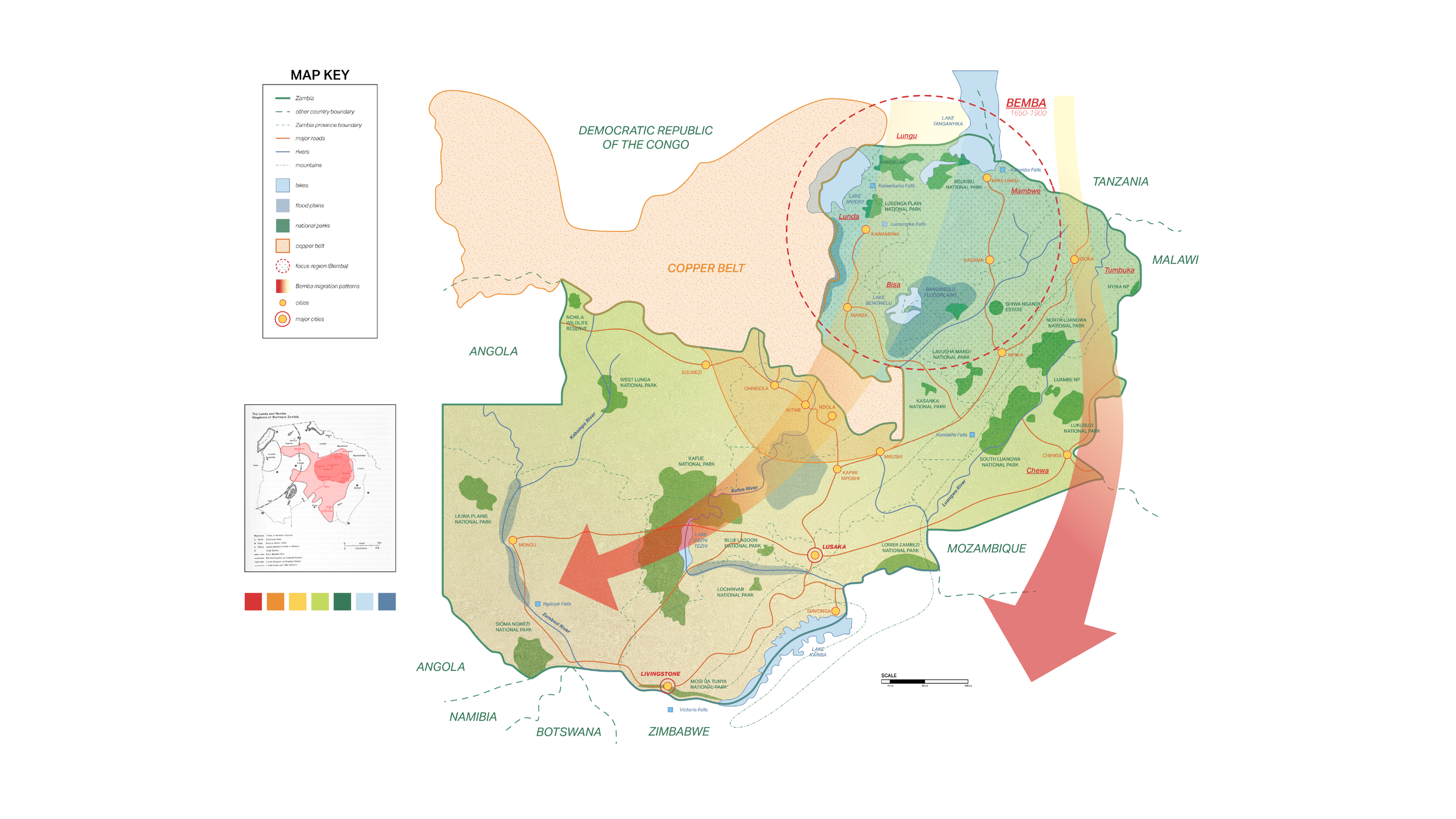

vernacular origins

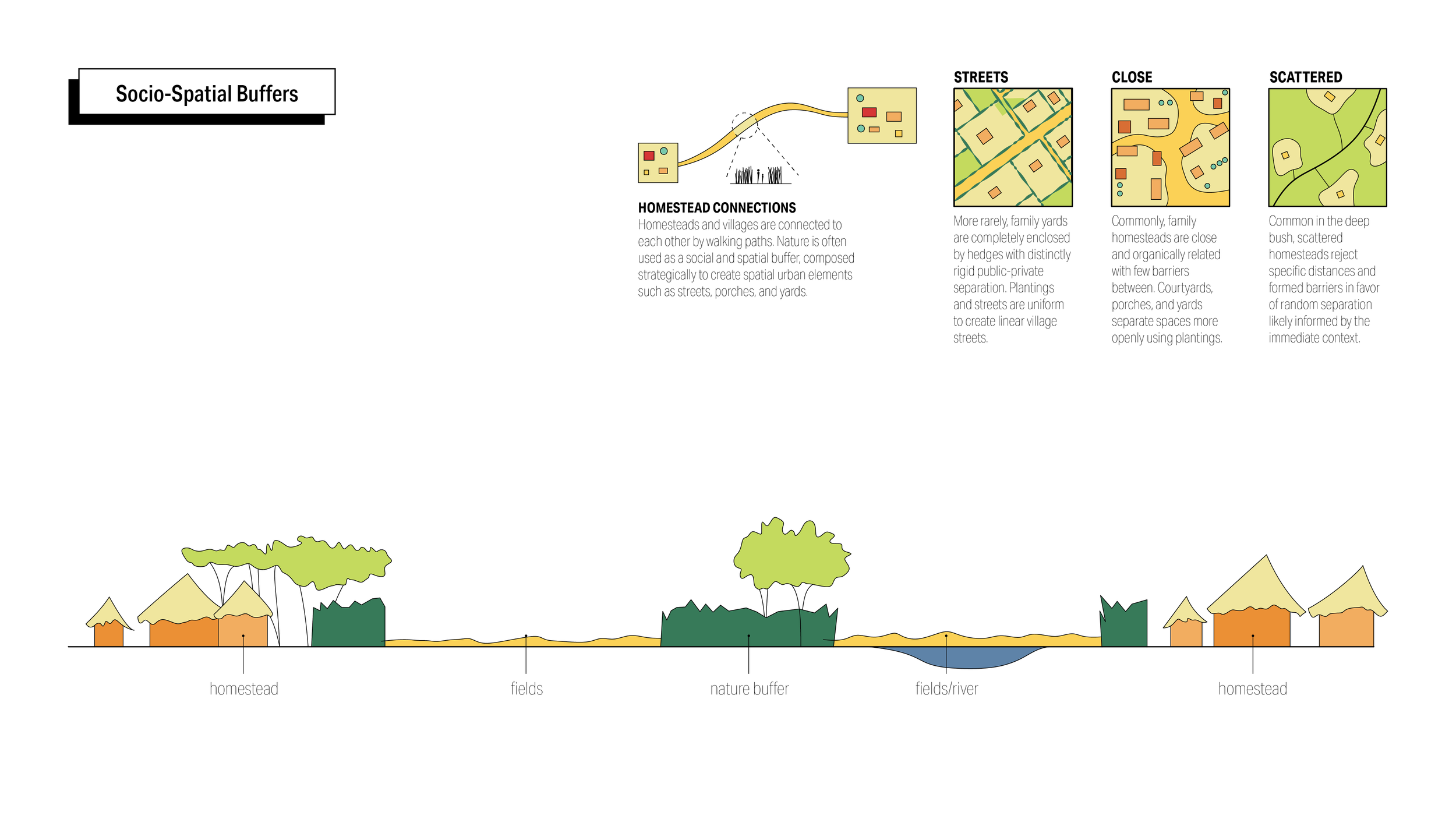

A close study of indigenous architecture and building practices can inform potential translations to modern contexts. Vernacular methods of labor and maintenance arose as a common thread between the assigned region of Luapula, Zambia and the eventual site of Jujuy, Argentina.

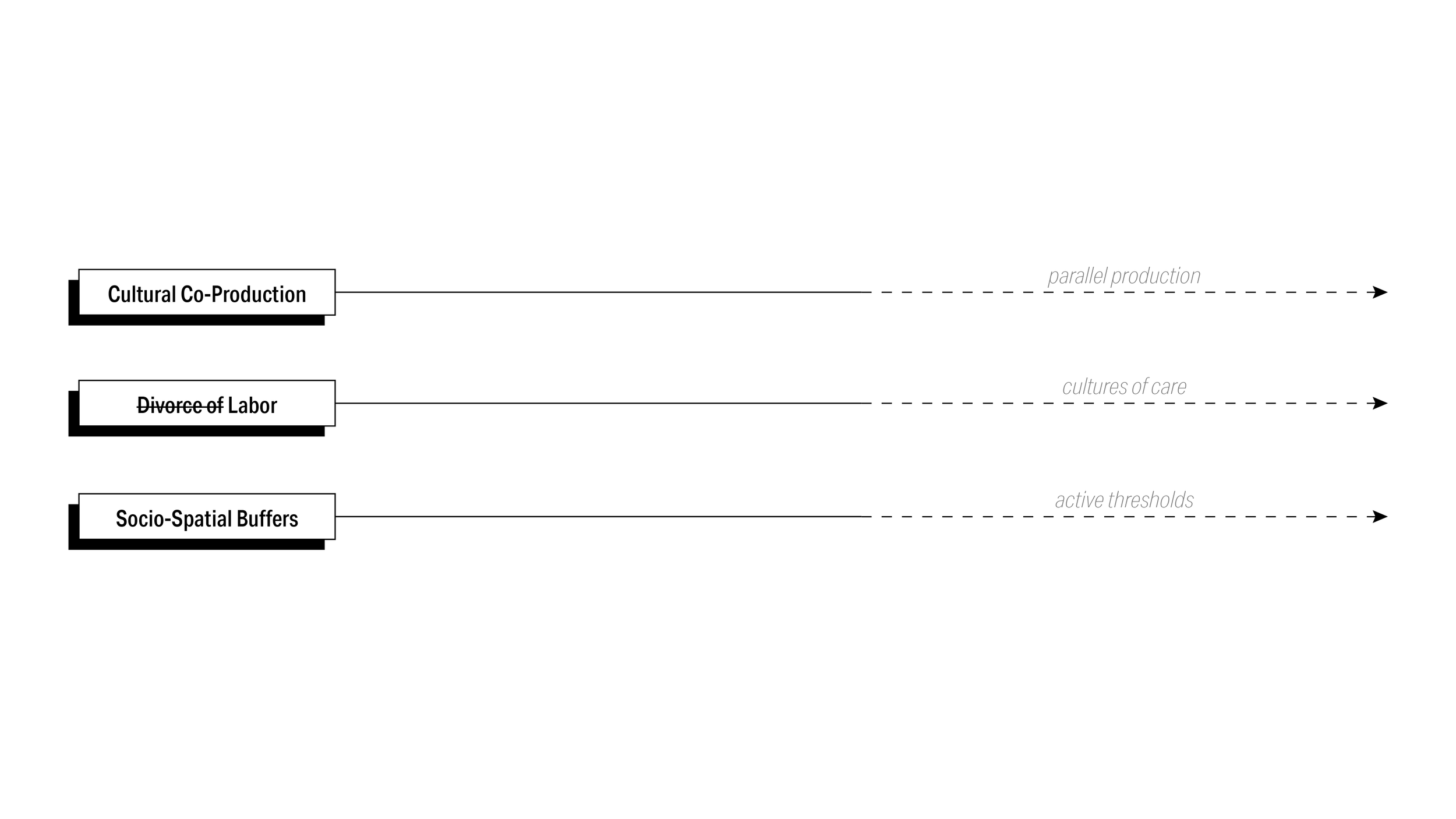

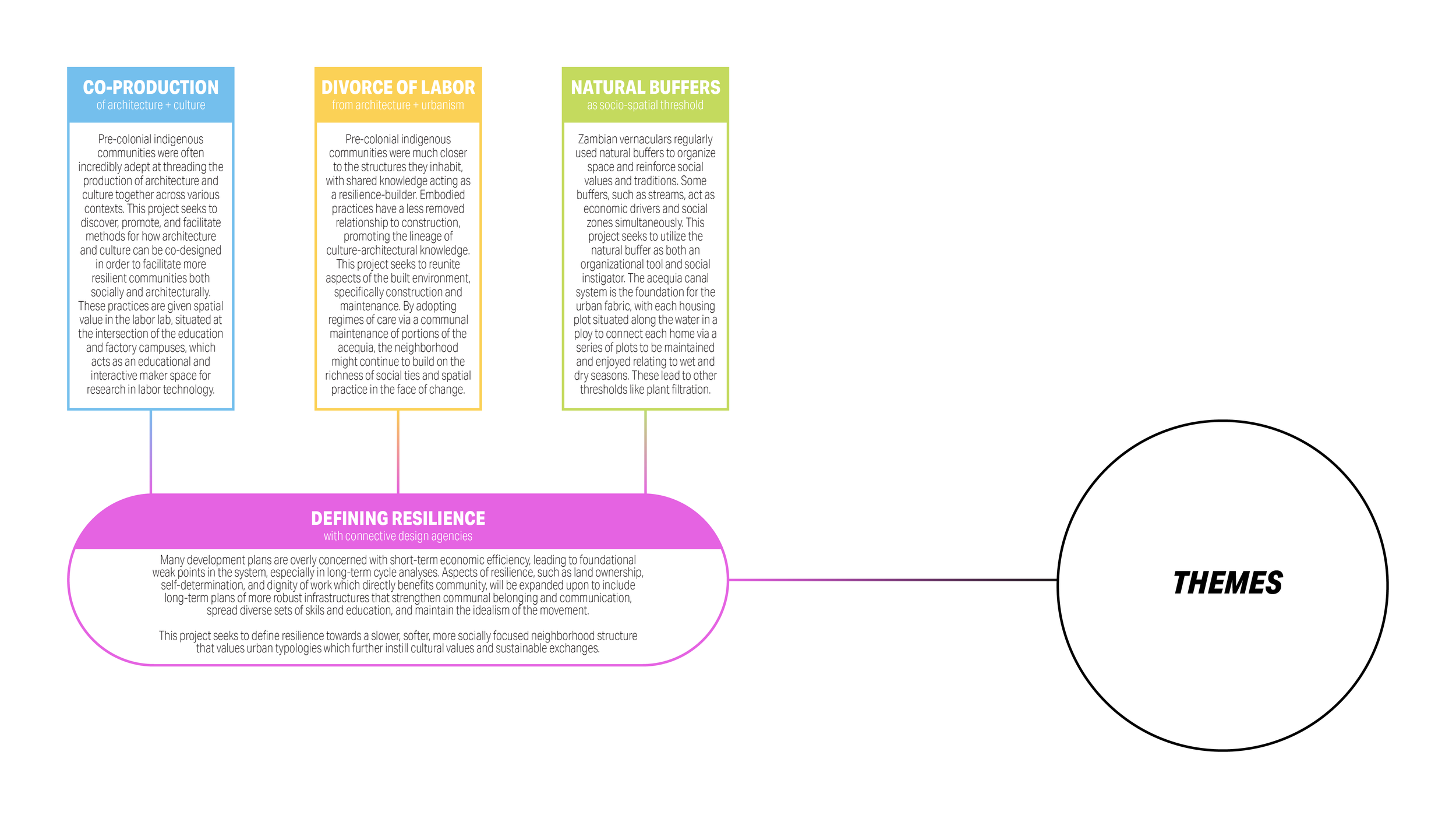

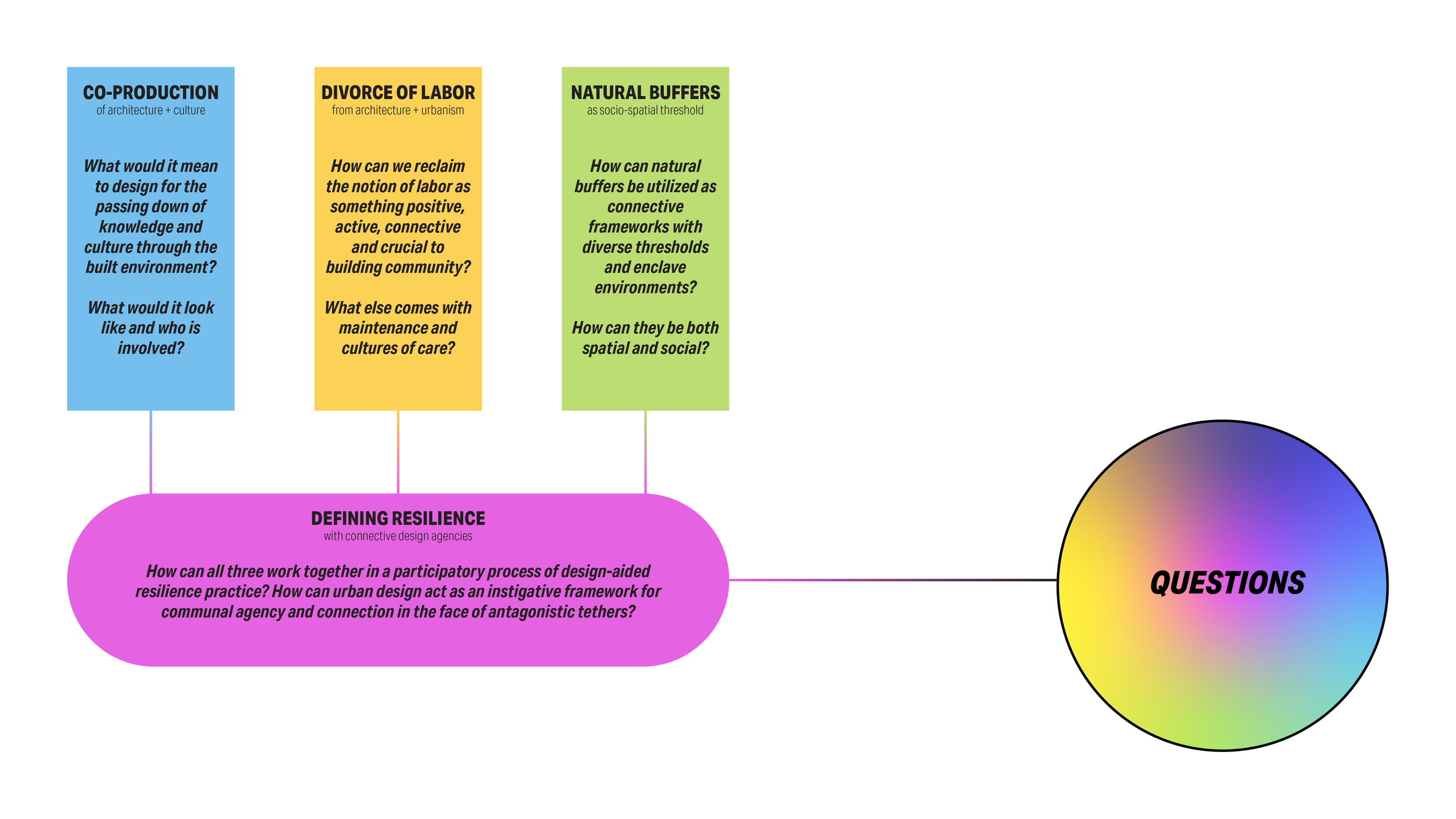

Three major interests drive the work from Zambian vernaculars to contemporary Argentina:

the coproduction of architecture and labor,

the role of labor and communal knowledge in that process, and

the ways natural buffers can be used to inform social and spatial organization.

This project argues that, together, the three encourage more resilient urban fabrics in the face of crisis or outside opposition.

Organización Barrial de Tupac Amaru

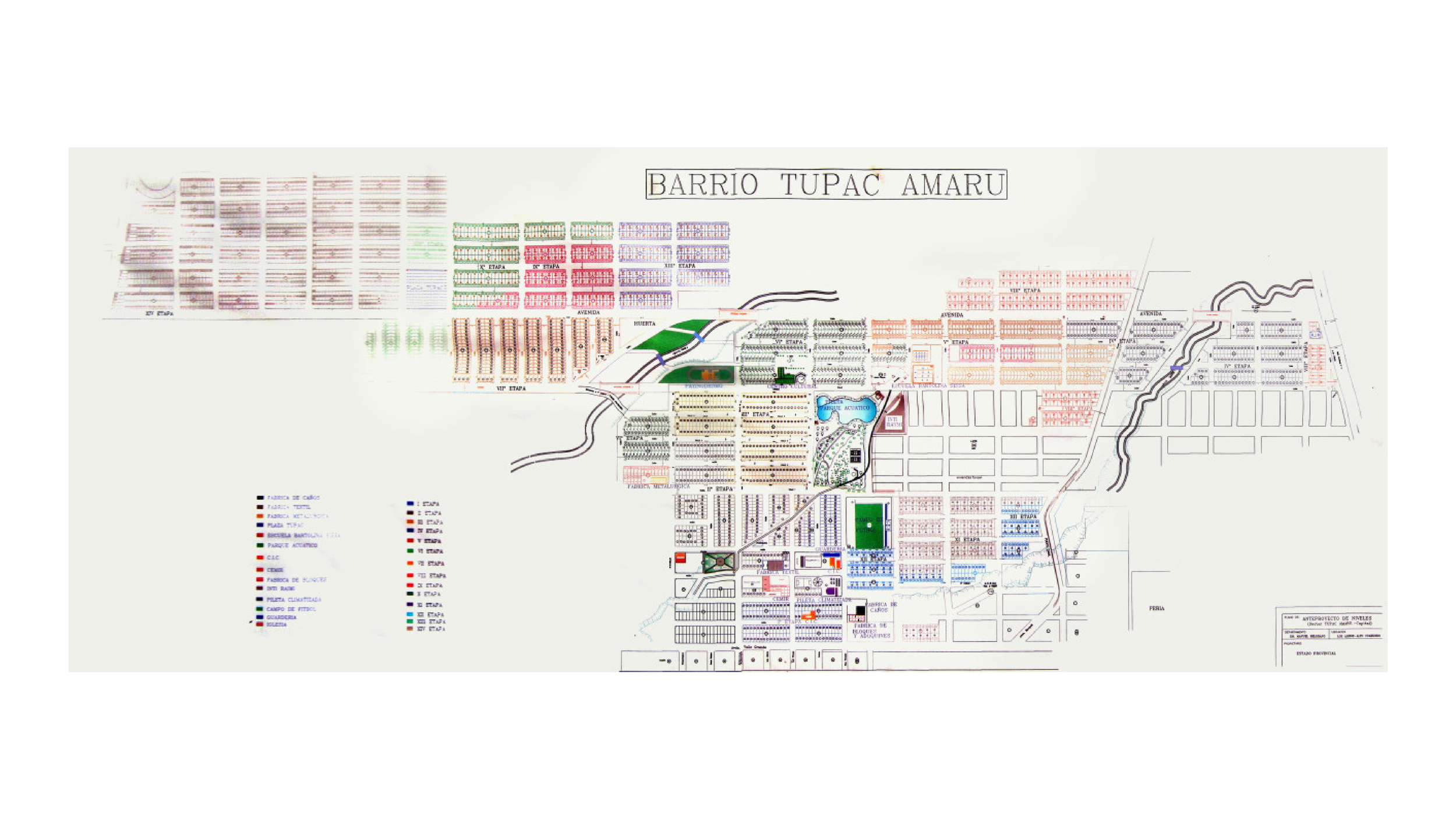

Alto Comedero is San Salvador’s largest and most densely populated neighborhood, primarily by indigenous peoples. To the south is “El Cantri,” a cheeky play on “country club,” founded and developed around 2003 by the Organización Barrial de Tupac Amaru.

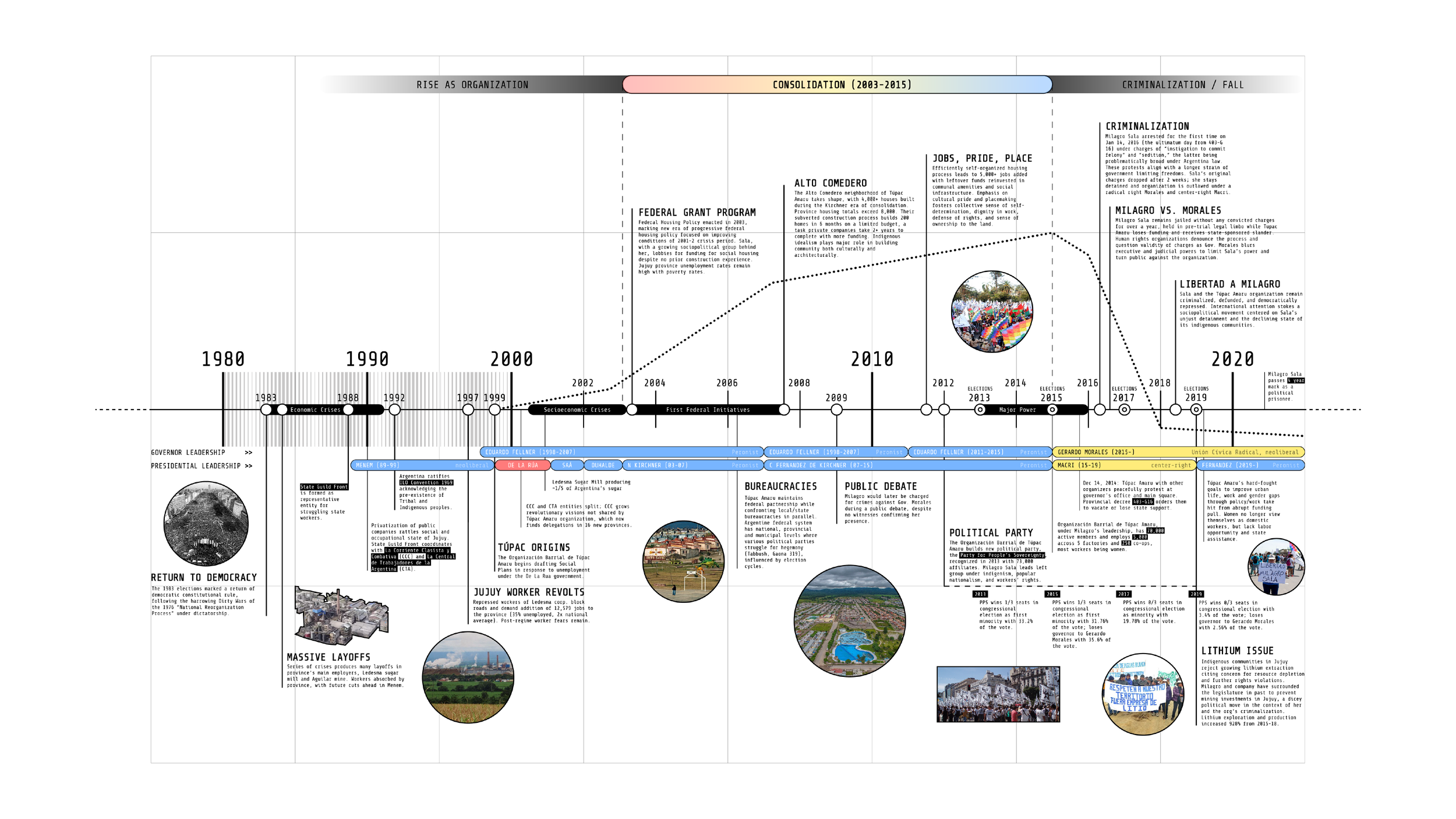

The OBTA was a direct response to socioeconomic crises (stemming from the military coup, Dirty Wars, and return to democracy) that promoted labor rights activism. Workers unions formed, OBTA branched off as a separate faction, and began organizing for federal funding.

Milagro Sala, as a visible leader, negotiated funds under the Kirchner government, leading to the OBTA adopting a cooperative model in order to receive funding and build the first round of homes quicker and cheaper than expected. This led to increased government support, with savings reinvested towards communal infrastructure and amenities.

They became politically active, forming a party and winning seats by 2015 when the political landscape shifted. Local governors now despised the organization and its power, with a top-to-bottom conservative shift in 2015 enabling the imprisonment of Milagro and criminalization of the entire organization. All funding and developments were halted, leaving the indigenous OBTA unsupported (and in some cases demonized).

The pool is now dry, with hundreds of homes left half-built.

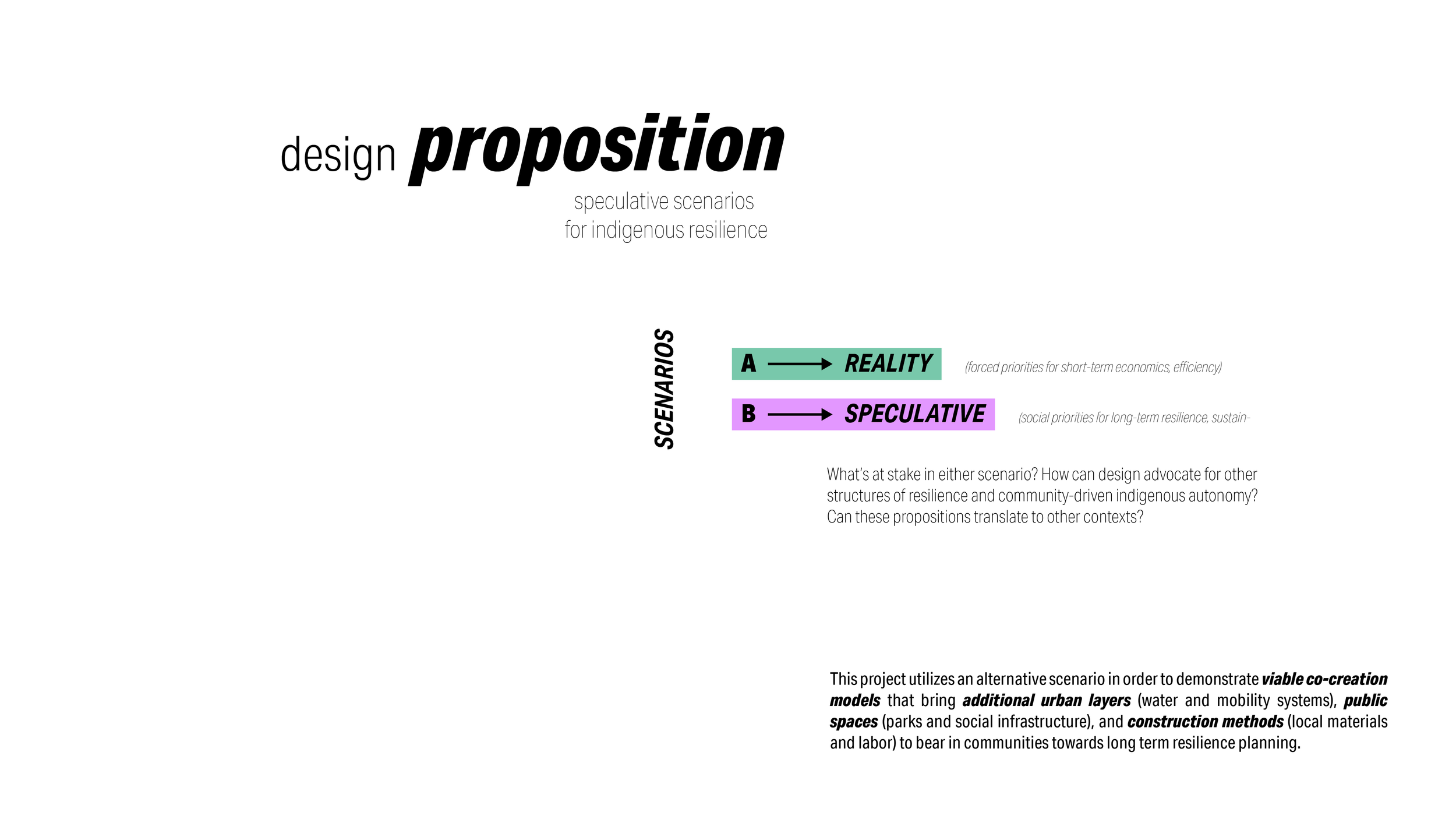

proposition

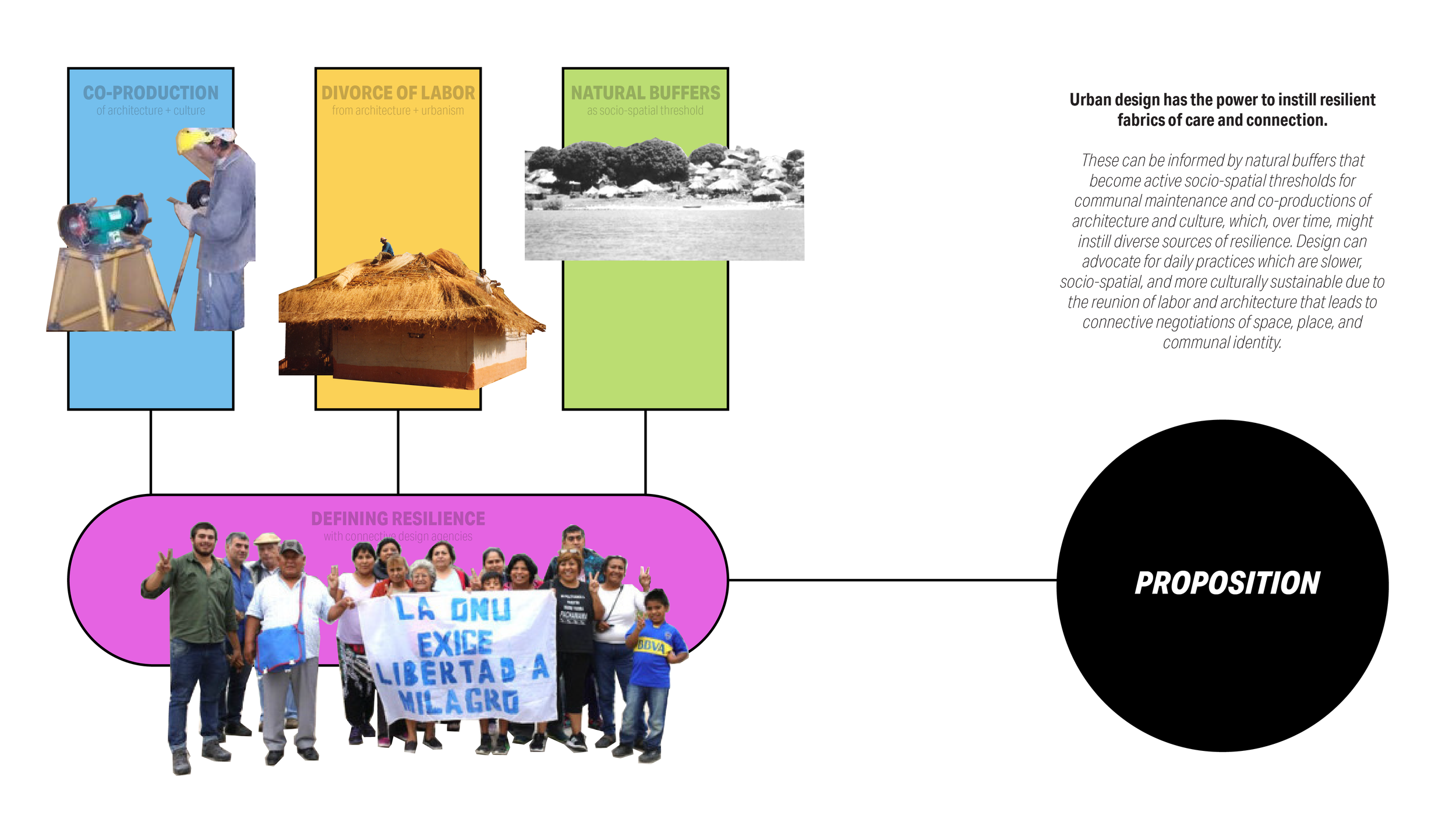

This proposition takes inspiration in the OBTA’s self-organization and the scope of design they achieved, looking for ways to provide a better outcome for their original goals.

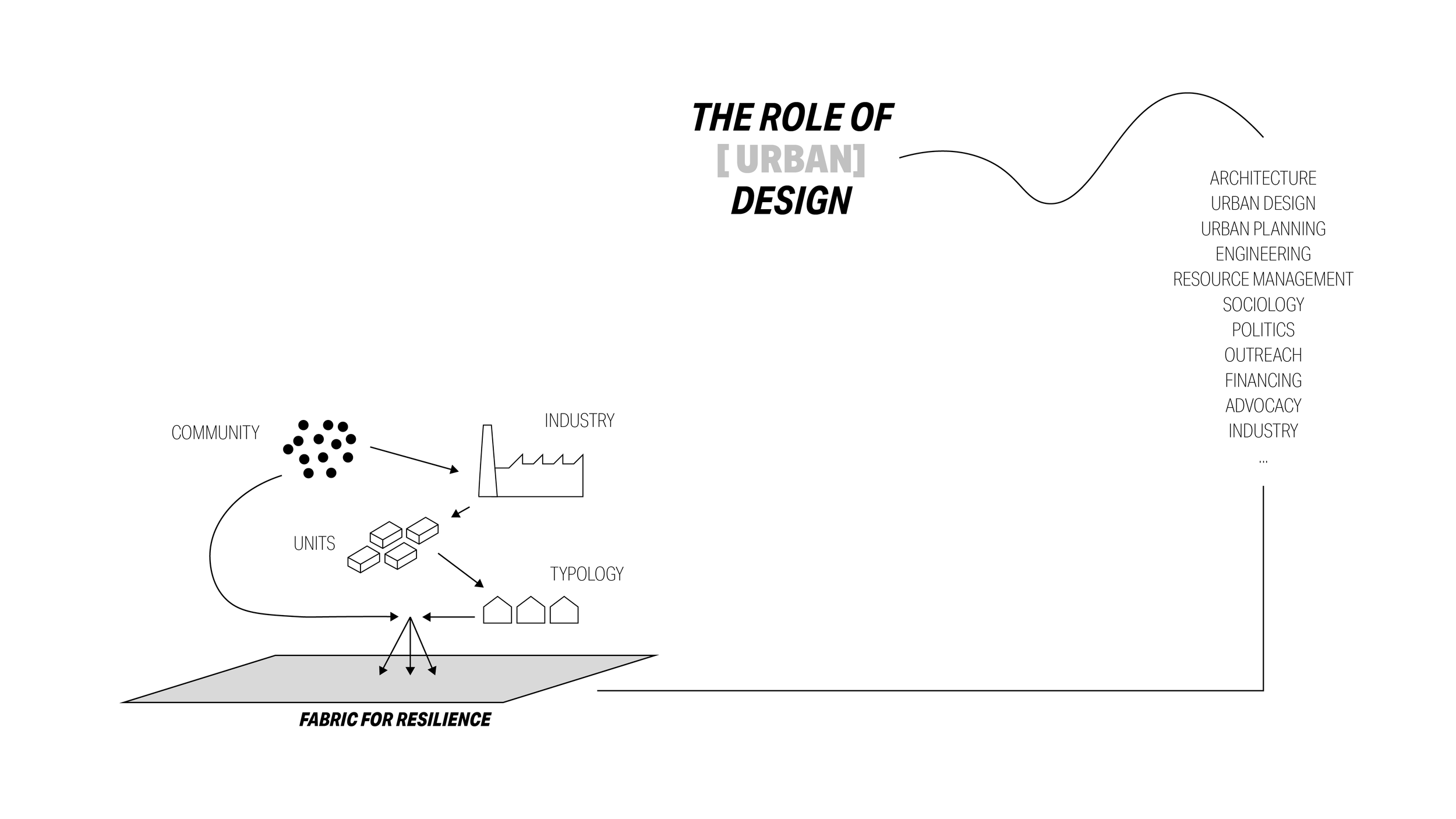

The conditions at play aren’t just unique to Argentina; these major shifts and responses often occur in other situations and contexts. Too often, a community or organization’s hope for success rests on single points of failure at the discretion of top-down tethers that are constantly shifting between allies and antagonists. How can this timeline be altered by design advocacy?

Above: tracing the flow of power through people, labor organizations, political landscapes, and material goods.

This proposition turns back the clock, entering the conversation the moment the first wave of funding was received. It pulls apart priorities forced upon Milagro and the OBTA in Scenario A, the reality, in order to respond differently in a speculative Scenario B, the proposition, where the organization’s original priorities are not weighed down by timelines and short-term economics from outside tethers.

Their story reveals how dependent architecture is on politi-economic power structures, and the influence they have over urban spaces and ‘othered’ populations. It is a fragile balance that can be transformed through design that values more embodied cycles of care and communal maintenance.

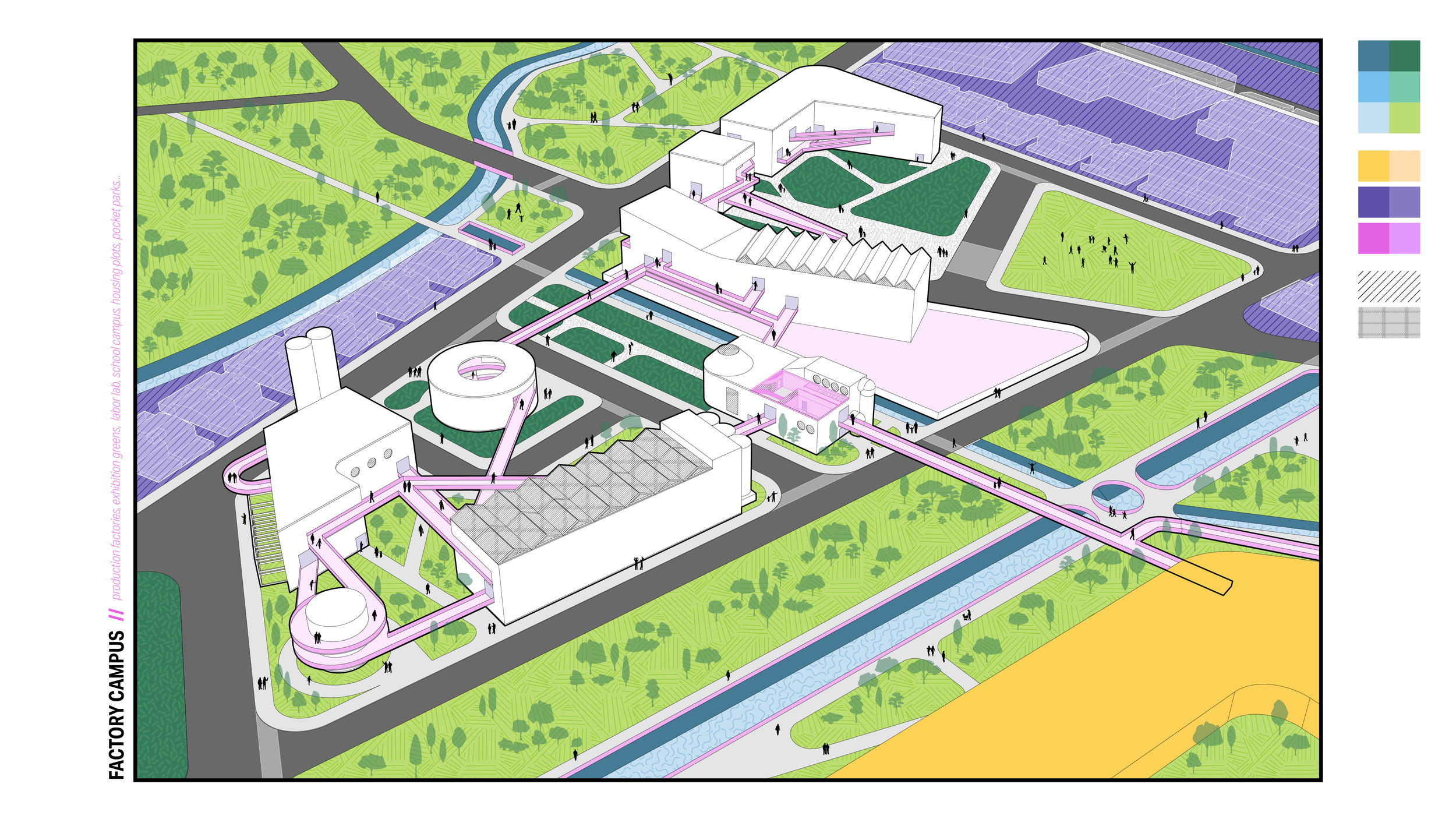

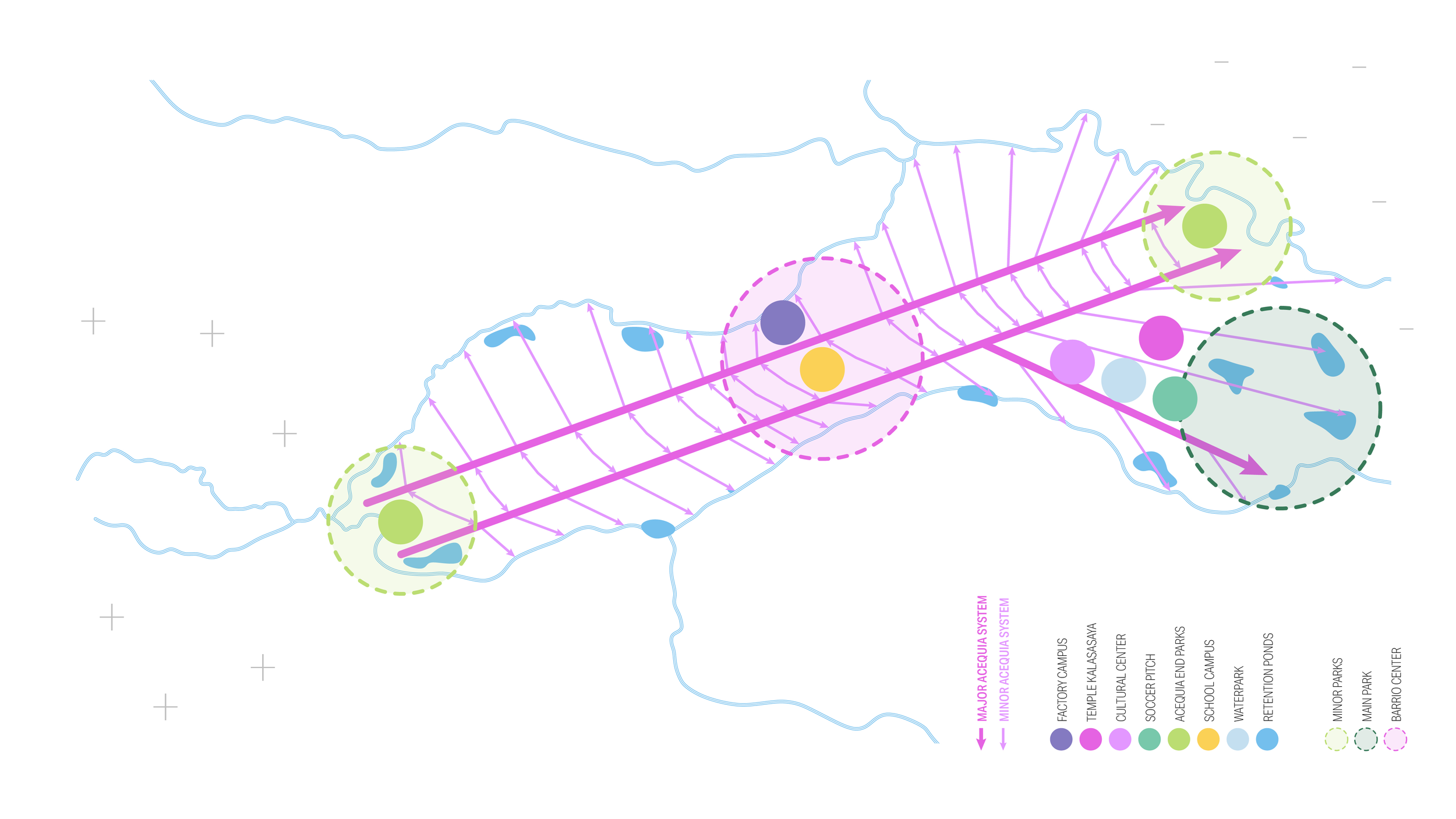

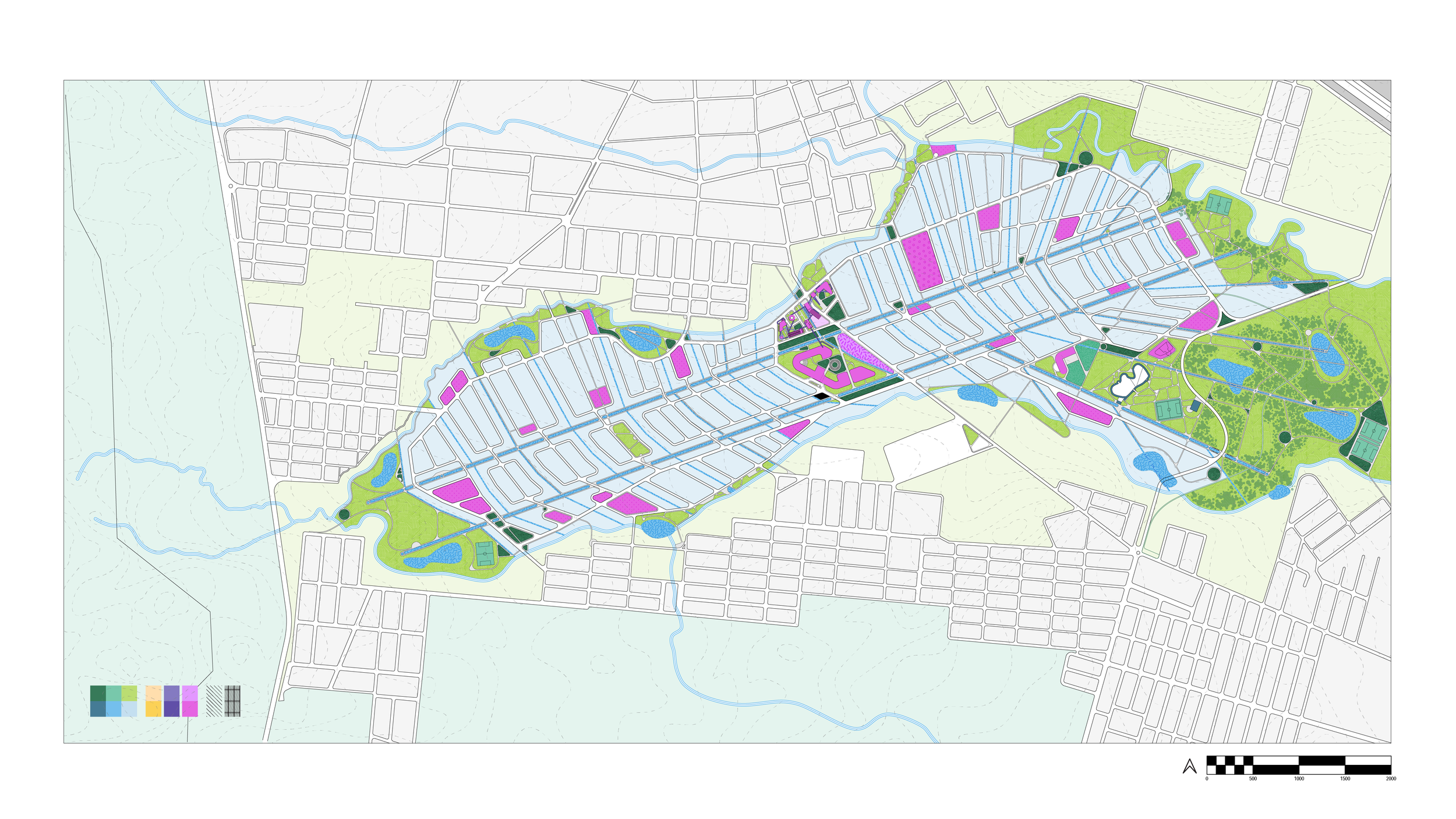

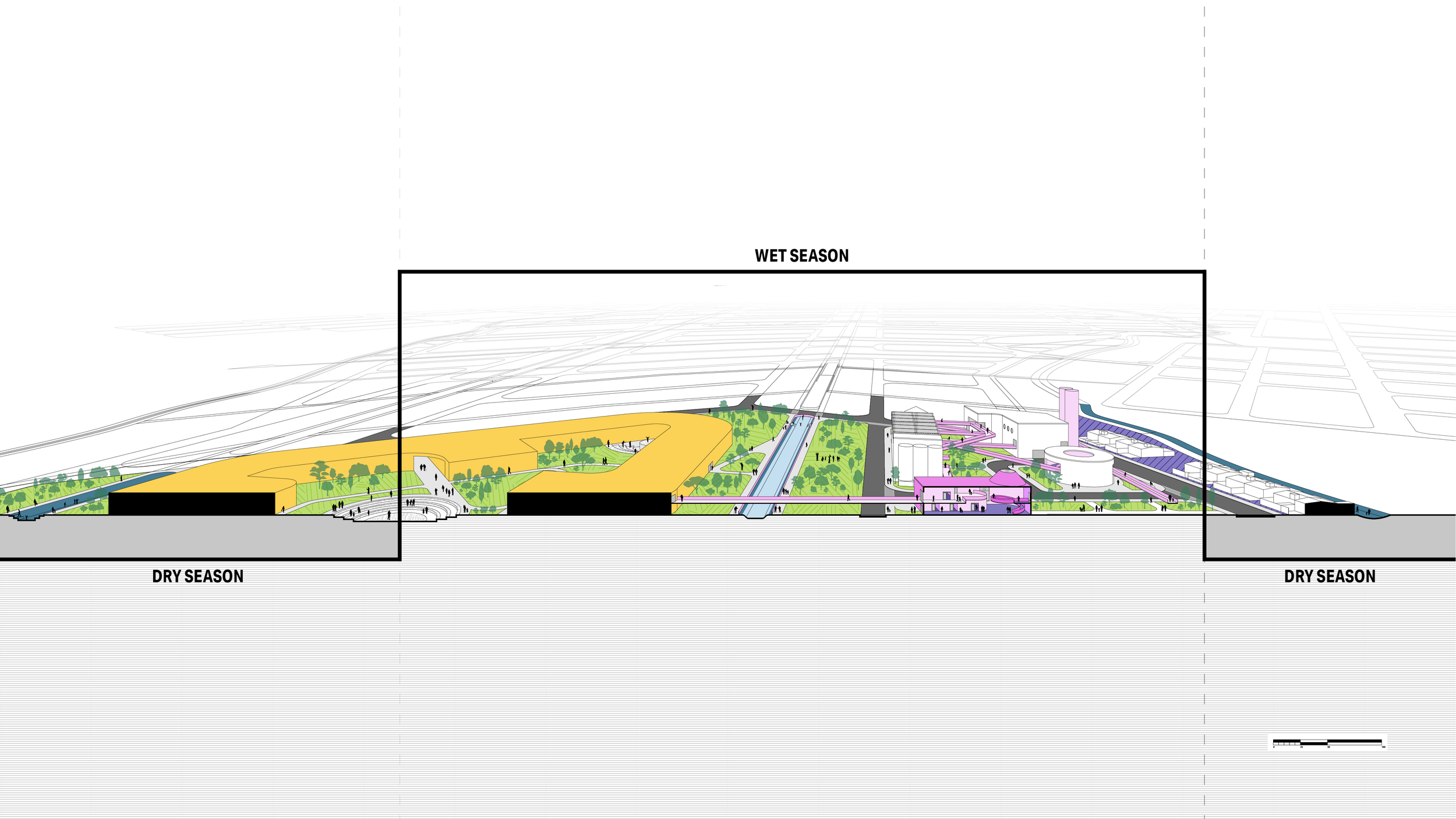

An eco-urban network of linked relationships sees the agency of designers meeting the goals of users. Taking aspects from the Zambian studies in natural thresholds and maintenance culture, this plan centers urban logic on the connective system—here an acequia, or social canal—as the driver for spatial organization and cultural resilience. Spaces for communal use, from cultural centers to recreation and religious zones, are distributed for maximum access and future expectancy. Thresholds inform constant negotiation, with resiliency measures in practice.

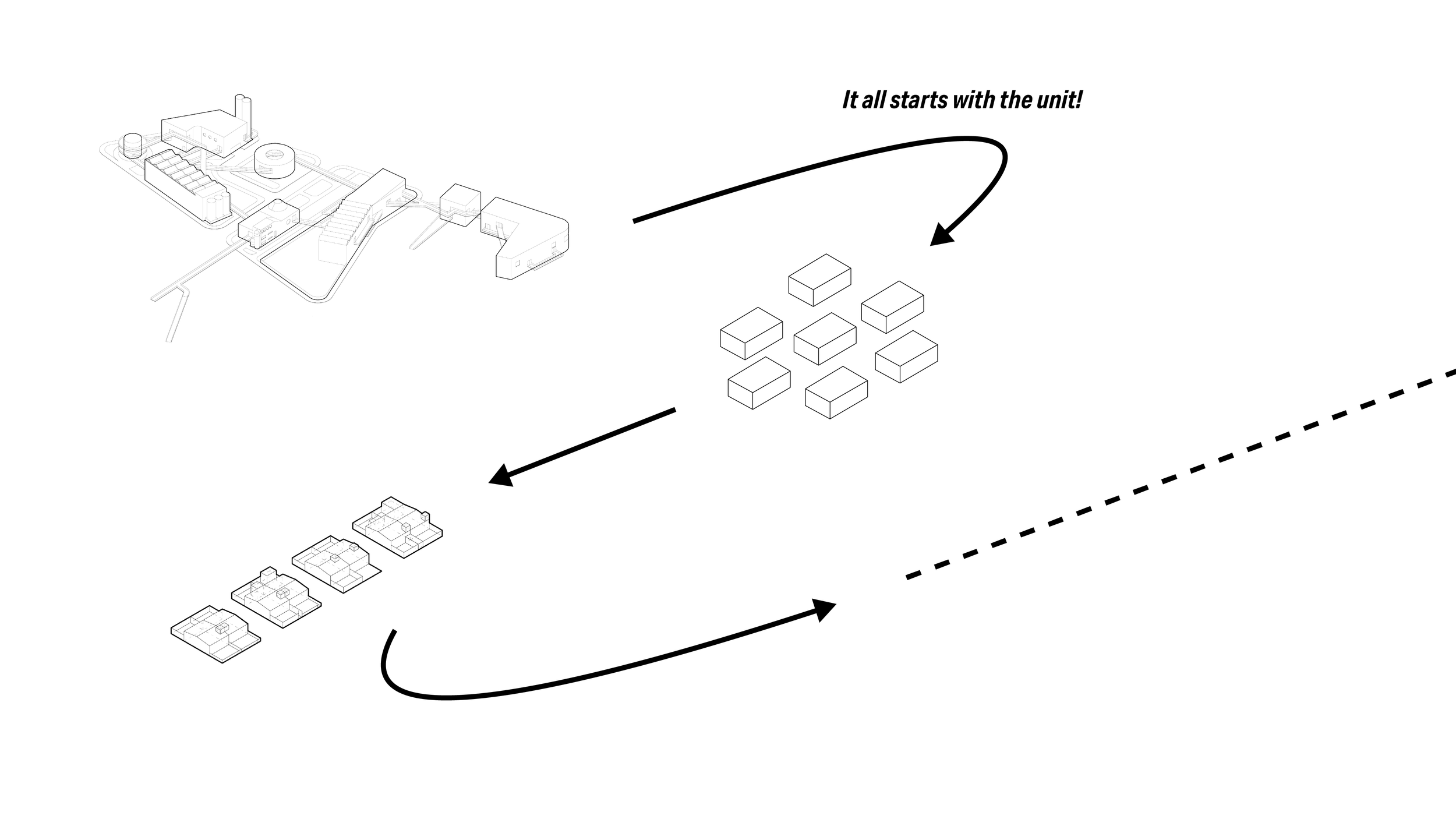

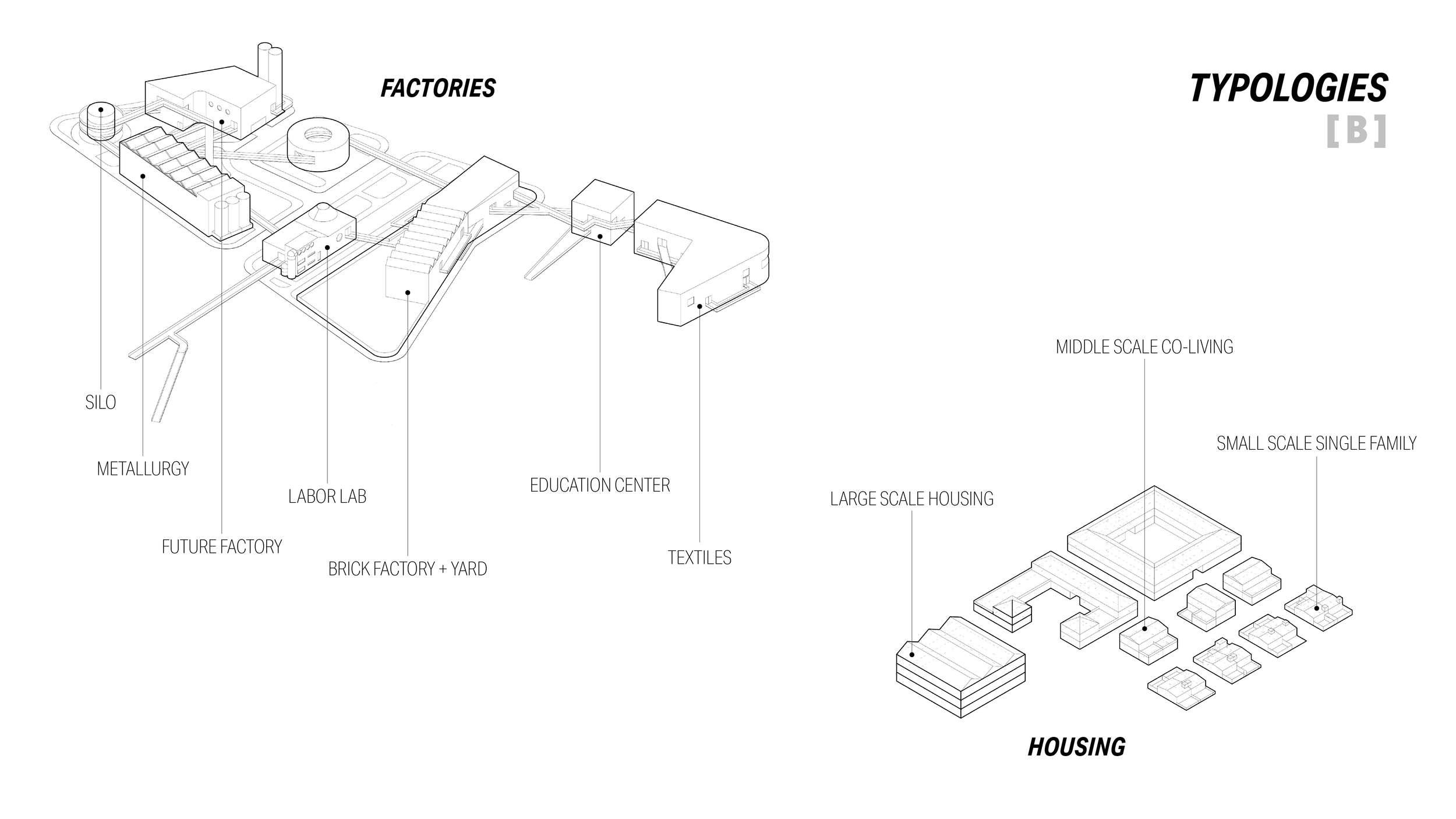

Scenario B uses two existing ditches as acequias—a communally-operated water stream that engenders mutual aid and collaboration, especially in times of crisis—as the guiding design principle. Streetscapes are entirely informed by both acequias, as homes and communal buildings all relate intimately to the running water and all they signify. Housing plots aim to connect as much as possible while retaining the highest degree of design agency possible; they are able to play with different scales and materials coming from the factory campus and labor labs, deploying various typologies across the barrio as they see fit.

The OBTA maintains material and expressive control; homes can be composed at various scales beyond the single type in Scenario A so as to explore different ways of living and laboring with dignity, pride, and care. Social infrastructures are emphasized both as a placemaking tool and source of resilience.

The factories now directly relate to the streetscape and school system—no longer a segregated or negative urban zone, but rather a source of pride, prosperity, and knowledge production. Elevated pathways encourage exploration and education, with green space and exhibition parks (light and dark green respectively) becoming part of an encouraging landscape for exchange. The collective makes use of design with their own agency.

Scenario B seeks to diversify the power structures at play in the original scenario so as to instill more balance and voice in the process. Expanded leadership visibility, additional support organizations, and redefined priorities are liberated from time crunches and economic pressures. It instead prioritizes the long-term development of cultures of care that maintain the ideals at the heart of OBTA while simultaneously preparing them to respond to the unpredictability of outside tethers and political antagonists.

Homes essentially attach themselves to the diverse canal systems as they travel downhill from west to east, connecting back to the original existing canals. The urban fabric is informed by pedestrian access along these canals, removing priority from the automobile to pedestrians and ecology. The factory and educational campuses remain at the center, attached to the widest canals and running parallel to the bracketed acequias. Each of the major elements are attached to the three widened acequias.

The Labor Lab is an incubator makerspace in action, where new tech is pushed to its limits and future factories explored. In Scenario A, the main unit was brick; something common and widely known. Stone laying, for example, can be taught and explored as a specialized skill that would fare much better for those seeking sought-after skill jobs (especially if funding ends and factories are closed).

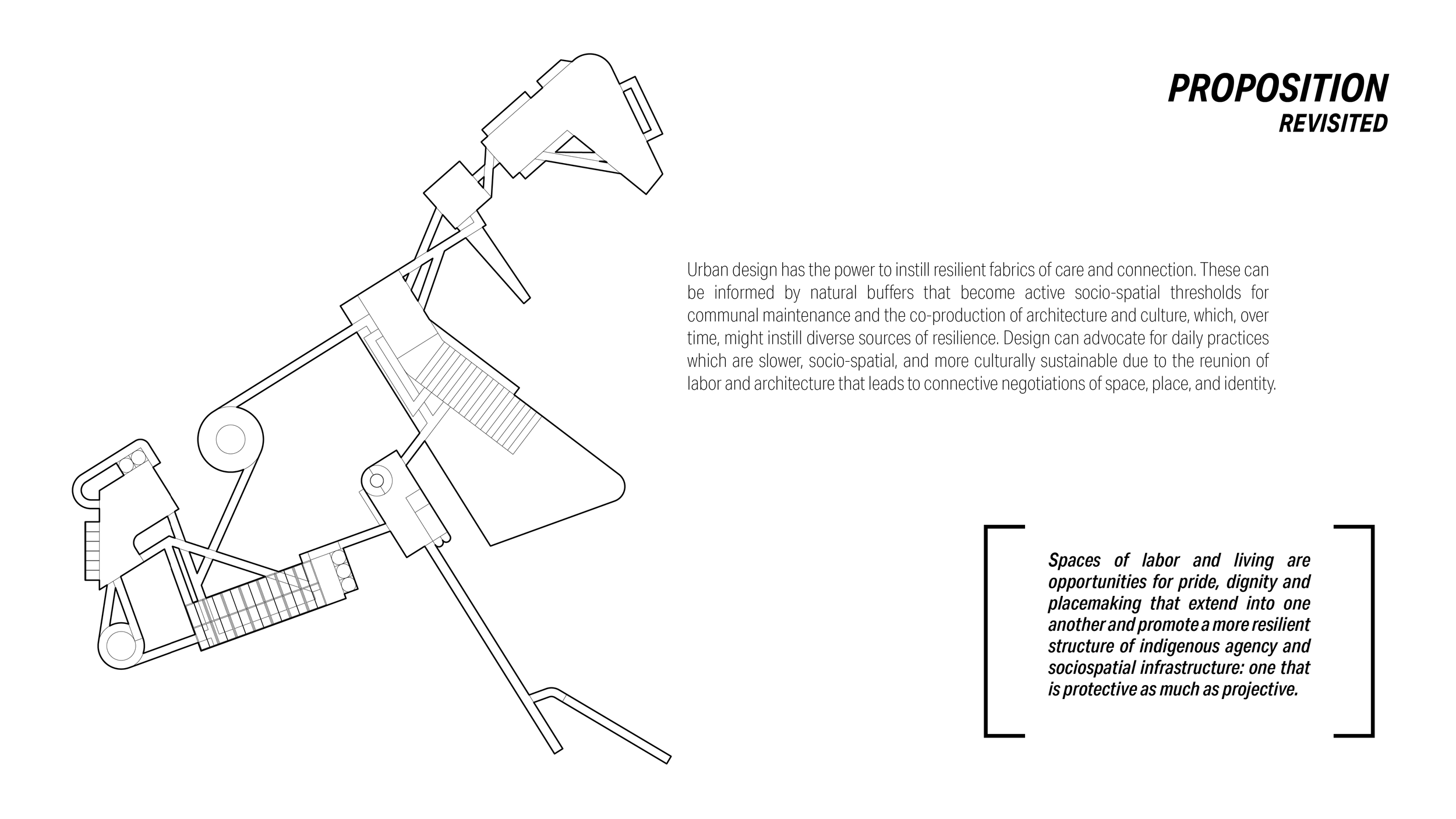

Urban design has the power to instill resilient fabrics of care and connection. These can be informed by natural buffers (like acequias) that become active thresholds for communal maintenance and the co-production of architecture and culture, which, over time, might instill diverse sources of resilience.

Design has the capability to advocate for daily practices which are slower, social, spatial, and more culturally sustainable due to the reunion of labor and architecture which can then lead to connective negotiations of space, place, and identity.

This is the value of the acequias; why they became the central component to the urban design. Acequias require responsibility, communication, and understanding, especially in times of crisis.

The nature of acequias encourage the maintenance of all those things, leading to a community that is more connected and therefore resilient. Democratic systems emerge and acequia members are responsible for cleaning their portion of the ditch. That is where social and cultural exchange takes place, often intergenerationally, along the sound of water moving slowly.

The acequia system is a mutually managed, meditative, and socially sustainable practice that brings people, resources, and histories together in the name of something much deeper, larger, and meaningful than the canals might first suggest.

This becomes the new network; a cyclical relationship between people and place, where urban design frameworks utilize natural thresholds as social drivers.

images

special thx

iman messado (for the Zambia collab & deep chats on life)

ellie ervin (for sitting together & becoming fast friends)